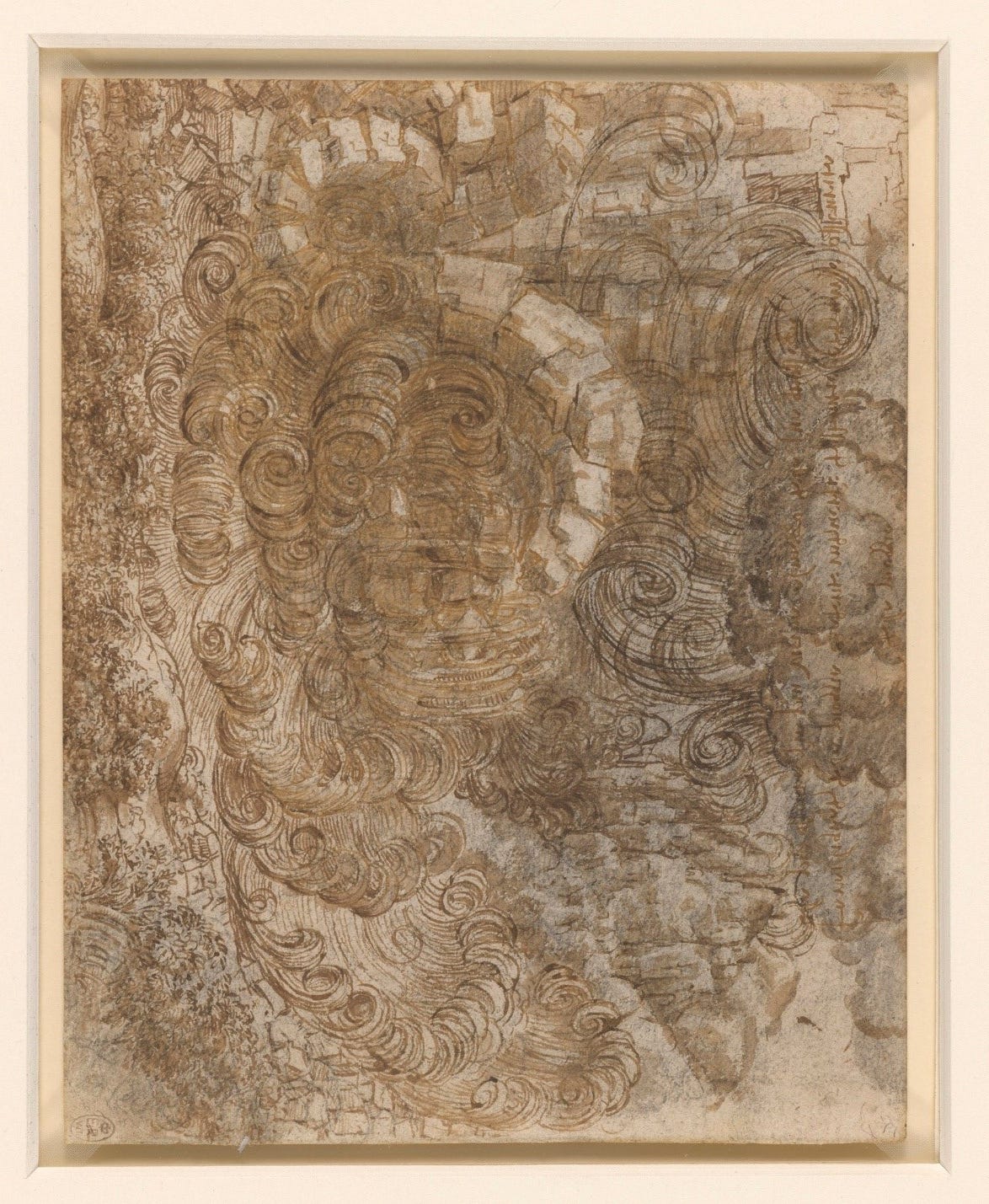

Leonardo da Vinci was not a simple man. Poring over his writings or gazing intently at his artworks, they seem to constantly reveal new features. In this series, I will be providing the key to Leonardo’s cognitive lockbox. As a man who is widely stated to have been born centuries before his proper time, Leonardo was forced to tread carefully when commenting on contentious topics. As a result of this careful treading, it has taken in excess of 500 years for a student of his work to ascend these newfound steps on the edifice of Leonardo’s worldview. Many understand that Leonardo had a deep appreciation for nature, but few know just how far this appreciation went. In the course of this and subsequent unveilings, I’ll demonstrate that Leonardo came to the understanding that nature is God, exactly what this understanding meant to him, and the implications of this understanding in interpreting his art. As one engages in such interpretation, many different, previously unappreciated aspects will come to the surface. A little-known sketch by Leonardo, pictured below, offers a wonderful analogy to such explorations. In a single graphic, one face emerges in many forms, dimensions, and positions.

(leonardodavinci.net, edited with Canva) Study of five grotesque heads

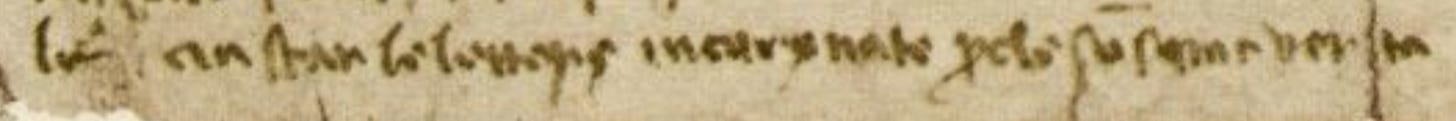

(leonardodavinci.net, cropped and edited with Canva)

In this first installment of The Latent Legacy of Leonardo, I’ll be investigating his philosophy. We’ll begin with a brief treatment of Leonardo’s genius, and then move on to an overview of the intellectual atmosphere of Renaissance Italy. Next, an extensive analysis of Leonardo’s notebooks will ensue, with an eye for uncovering his thoughts on various topics ranging from human learning to the universal soul. After touching on Leonardo’s expert awareness of anatomy, we’ll move to his essential reinvention of the figure of John the Baptist. Only then, will we be able to appreciate the philosophical secrets embedded in his artworks, which will be the final topic covered in this posting.

Leonardo the Genius

Let’s start by stating the obvious: only an incredibly intelligent and capable person could create a puzzle that has taken more than 500 years to solve, despite the best efforts of countless researchers. Considering this, our first task must be to appreciate Leonardo’s position as a genius polymath. Justifiably, given its exquisite quality, Leonardo is best known for his art. Sometimes overlooked however is Leonardo’s sheer breadth of study. One of his many interests was mathematics, about which he wrote, “[t]he man who blames the supreme certainty of mathematics feeds on confusion…” (Richter, 219). Leonardo befriended a Franciscan monk by the name of Luca Pacioli (who is known as the father of accounting), and the two men went on to write a book together titled De Divina Proportione. The book laid bare the pair’s incredible expertise on both geometry and proportions, and later Leonardo also contributed to Pacioli’s De Viribus Quantitatis, a work focused more on mathematical tricks and puzzles. Another field where Leonardo displayed his talent was that of mechanical engineering. His notebooks are bursting with detailed drawings of complex machinery, with some being so advanced they couldn’t be fabricated within his lifetime. Among other things, Leonardo designed the first parachute, submarine, scuba suit, military tank, wheel-lock musket, and even a musical instrument called the viola organista. Possibly the most impressing facet of the Renaissance man’s studies was his striking apprehension of the natural world. He wrote and drew on subjects including botany, geology, astronomy, cartography, and the unique properties of water. Leonardo’s knowledge of the relationship between gravity and acceleration led aeronautics expert Mory Gharib to remark that his writing on the subject, “demonstrates just how far ahead his thinking was…” (cnet.com, 2013). I could go on for pages describing Leonardo’s immense contributions to numerous fields of study. Such a detailing will be forgone, in the hopes that one can appreciate through this short summary Leonardo’s position as a true genius. Now, with this in mind, let us explore the reasons why Leonardo was forced to hide his philosophy in his notebooks and art, rather than expound those views openly.

Leonardo’s Environment

Renaissance Italy was a time of great conflict between humanists and traditionalist Catholics. In many ways, it was a time of newfound freedom, where for the first time in centuries students were able to engage with classical works, without the fear of repercussions. Analyzing Greco-Roman literature or painting pagan mythological scenes, however, pales in controversiality to the heretical messages contained within Leonardo’s notebooks and artworks. He spent his earlier years in Florence, and this period is typically remembered as a time when the Medici rulers allowed citizens the latitude to respectfully challenge certain aspects of Catholic teaching. That being said, this was certainly not a time when one could openly proclaim nature to be our God, or argue that the Christian conception of divinity is false to its core, as Leonardo secretly did. While Florence was something of a haven (prior to 1494) for students of experience like Leonardo, sinister characters such as Girolamo Savonarola continued to wield outsize influence. Various royal families and religious officials vied for control of the Italian city states, and with the widespread hostilities, one could never be sure who would come out on top. When Savonarola the venomous preacher took Florence in the mid 1490’s, the Bonfire of the Vanities which followed was not an aberration, but rather a return to what had been the status quo for centuries. Leonardo, being the genius he was, surely was aware that his works (and possibly himself as well) would pay the ultimate price (burning), should they contain easily discernible heretical themes and traditionalists gain access to them. It remains highly doubtful that the rulers most supportive of the new humanism, such as those of the Medici and Sforza clans, would allow Leonardo to openly declare his understandings, whether through the medium of writing or art. Considering this environment in Renaissance Italy, Leonardo’s decision to conceal his philosophy within complex explanations and cryptic symbols should be understood as his only logical choice. To fail in this task would mean that his philosophy should die alongside his physical body, an outcome unacceptable to Leonardo. After all, as he writes, one should “[a]void studies of which the result dies with the worker” (Richter, 221).

A Critique of Jean Paul Richter’s Translation

Before diving into Leonardo’s notebooks, I need to make a quick note on the translation I’m relying most heavily upon, that of Jean Paul Richter (1883). I’ve discovered that Richter makes a number of decisions while translating that seem to alter or misrepresent Leonardo’s perception of the universe. Perhaps the most obvious case is Richter’s insertion of two sentence-long statements focused specifically on God, at the beginning of a section dealing with Leonardo’s philosophy, and providing no context on what Leonardo understands God to be. In fact, the first translated line in this section is provided in a remarkably misleading manner, as despite Leonardo seeming to refer to temporal lords (as he does in every other instance in which he uses “Signore”), Richter labels it as a “prayer to God”. Richter also adds capitalizations which convey meanings distinct from the uncapitalized characters found within Leonardo’s notebooks, though Richter does typically make note of this when he does so. I’ll be removing false capitalizations and making note of them by inserting brackets, except in the case of “nature”, which I simply leave lower case, as there are many instances of the term being improperly capitalized by Richter. When considering Richter’s motivation for making such decisions, one’s thoughts must turn to his upbringing and schooling. As the son of a theologian and a man who studied to be the same, it seems Richter has proved Leonardo’s proposition that “… often a master’s work resembles himself” (Richter, Loc. 3297). Richter may very well have been a master, but he should never have allowed his own biases to influence the content or structure of his translations. I hope to right this wrong by presenting Leonardo true to his own writing, and may have an advantage in that my own predispositions are far more similar to Leonardo’s than a theologian like Richter’s.

Notebook Philosophy: Nature

Leonardo’s notebooks are incredibly challenging to decipher. In addition to using mirrored characters and writing from right to left, he frequently makes complex associations between various topics. As readers engage deeply with the text of his notebooks over some time, they will likely come to appreciate his incredible consistency. Leonardo had a steadfast worldview, but one that would surely result in his death, should he express it openly. As I reveal the cleverly composed philosophical tenets embedded in his notebooks, keep in mind (as described above) the times that Leonardo lived in. Leonardo’s philosophy was such that even to write it in easily decipherable text was to risk death, or possibly worse, an officially ordered burning of his life’s work. With this in mind, let us begin with the most fitting starting point for any exploration of Leonardo’s worldview; his treatment of nature. For Leonardo, nature is an entity with desires, and one that intentionally creates. He writes that, “…nature varies the seed according to the variety of the things she desires to produce in the world” (Richter, 228). This understanding of nature as an intentional creator extends also to the deaths of living things. On death he notes that nature “…is more ready and more swift in her creating, than time in his destruction; and so she has ordained that many animals shall be food for others” (Richter, 235). Nature causes death in more ways than simply carnivorous feasts. Leonardo states that “…this not satisfying her desire, to the same end she frequently sends forth certain poisonous and pestilential vapors upon the vast increase and congregation of animals; and most of all upon men, who increase vastly because other animals do not feed upon them” (Richter, 235). Essentially, nature must provide for the deaths of living things because “[o]ur life is made by the death of others” (Richter, 105). In his writing, “…earth therefore seeks to lose its life, desiring only continual reproduction” (Richter, 235), he keys us into his belief that the earth itself is an extension of nature.

So, nature creates life and death because she desires them, but what exactly is nature for Leonardo? He writes that, “…all that the eye can see…” is “…every object produced by nature or resulting from the fortuitous actions of men…” (Richter, Loc. 2817). In other words, everything that exists is either produced by nature or by men, so anything that is not fabricated by people must therefore be a creation of nature. This extends even to men and animals themselves. The physical characteristics of men are “…works of nature…” (Richter, Loc. 2991), and animals are “…the image of the world” (Richter, 234-235), which we established earlier as an extension of nature. In a critique of those who stubbornly rely on the teachings of respected authorities, Leonardo humorously writes that such people are “…little indebted to nature” (Richter, Loc. 253), yet another indication of his belief that nature creates humans. One more example of Leonardo’s appreciation for nature is his writing that “…the Universe…” is “…[t]he grandest of all books…” (Nuland, 63), though possibly controversial in its seeming diminishment of those supposedly holy Catholic scriptures.

Leonardo believed that the central importance he placed on nature was one that should be adopted by all others who claim to seek an understanding and/or accurate representation of the world they live in. In fact, failing to focus on nature and instead turning to the works of men was understood by Leonardo to relegate such artists to a second-class status of sorts. He writes that, “…those who only study the authorities and not the works of nature are descendants but not sons of nature the mistress of all great authors” (Richter, Loc. 3734). Leonardo’s praise of nature elevates “her” far above humans in creative capacity and ability. He notes that human ingenuity “…will never devise any inventions more beautiful, nor more simple, nor more to the purpose than [n]ature does…” (Richter, 101). The creative power of nature is not a supernatural influence for Leonardo, but instead manifests itself through the natural functions of bodies. For example, with respect to the formative process of humans in the womb, nature “…puts into them the soul of the body…” (Richter, 101), and the mother’s soul then provides the necessary instruction to the “dormant” soul of the infant. I’ll engage in a thorough detailing of Leonardo’s understanding of the soul later on, but the important takeaway here is that nature provides the souls for peoples’ bodies, and those souls produce the forms of the bodies of infants, meaning that nature is the creator of men.

Despite nature’s status in Leonardo’s philosophy as the ultimate and perfect creator and teacher, he does not assign nature the ability to manifest things out of thin air. Instead, nature must abide by the law of cause and effect without exception. A nice illustration of this point is Leonardo’s analysis of seashells he found on mountains throughout Italy. His empirically sound argument that the shells must be there because the mountains had once been underwater effectively disproves the Christian notion of the creation of the earth in seven days, but that is not of interest at this time. Instead, let’s focus on his treatment of the proposition that nature could spontaneously produce weathered shells on mountains; “…such an opinion cannot exist in a brain of reason…” (Richter, 164). According to Leonardo’s understanding, it is preposterous that nature could simply invent an effect without cause. This is because nature operates according to the principle of necessity. “O stupendous necessity…”, we read, “…by thy laws thou dost compel every effect to be the direct result of its cause, by the shortest path” (Richter, Loc. 320). We also read, “[n]ecessity is the mistress and guide of nature” and “[n]ecessity is the theme and the inventress, the eternal curb and law of nature” (Richter, 215). Taken together, Leonardo’s notes clearly indicate that the law of nature is cause and effect. Another way of communicating this is Leonardo’s writing that, “[t]here is nothing in all nature without its reason” (Einstein, xv). Everything which exists should be considered as an effect that results from specific causes. Some readers may be pondering the possibility that Leonardo did believe in a God separate from nature, and that such a God may have ordered nature according to the principle of cause and effect. The following writing by Leonardo should put to rest such a contemplation. Firstly, “[n]ature never breaks her own laws” (Mccurdy, 55), and secondly, “[n]ature is constrained by the cause of her laws which dwells inborn in her” (Baring, 532). From the first quote we learn that Leonardo believes these are nature’s own laws, not laws ordained by some other entity. From the second we learn that nature herself is the cause of her laws; nature is responsible for its own existence and consistent order.

Considering nature’s law of cause and effect, let us analyze Leonardo’s writing, “[a]dmirable impartiality of [t]hine, [t]hou first [m]over; [t]hou hast not permitted that any force should fail of the order or quality of its necessary results” (Richter, 215). Here, the “first mover” is clearly held to the law of cause and effect. As all life has already been established as coming from nature, if we evaluate this alongside Leonardo’s writing that “[t]he motive power is the cause of all life” (Richter, 216), it becomes apparent that the “first mover” is nature herself. If nature and her creations are everything that exists besides human inventions, and nature’s law of cause and effect produces those things, then can the lives of people or animals be anything more than simply a product of chance? Leonardo’s thoughts on this mystery shine through, when he writes (as cited earlier) that fools “…are little indebted to [n]ature, since it is only by chance that they wear the human form and without it I might class them with the herds of beasts” (Richter, Loc. 253-261). For Leonardo, even one’s species of life form is a product of chance resulting from cause and effect.

Before moving on to the next topic, let us dwell for a moment longer on the earth. We’ve already established that for Leonardo, earth is an extension of nature. However, he goes further, communicating conclusively that, “[t]he globe [is] an organism”, because “[n]othing originates in a spot where there is no sentient, vegetable and rational life…” (Richter, 167). When considered alongside his writing that “[t]he sun gives spirit and life to plants and the earth nourishes them with moisture” (Richter, Loc. 2313), a philosophy of the utmost reverence for our natural world as the ultimate creator emerges. Nature produces seemingly infinite organisms which are nourished by bodies also created by nature; nature is responsible for the fact, particulars, and rules of every thing’s existence.

Notebook Philosophy: Understanding and Experience

Leonardo certainly had a special reverence for nature, but how did he come to his understanding of the universe? Furthermore, what does it mean to come to an understanding in the first place? For Leonardo, understanding comes as a product of experience. We will begin with a brief description of understanding, and then move on to the concept of experience as detailed by Leonardo. His claim that, “[t]he greatest deception men suffer is from their own opinions” (Richter, 223), seems a proper place for beginning this discussion. We must transcend our own personal opinions if we hope to arrive at a true comprehension of any topic. This sentiment is again represented in his writing that, “[y]ou do ill if you praise, and still worse if you reprove in a matter you do not understand” (Richter, 222). Leonardo hopes that one might come to a genuine understanding before commenting on anything, and clearly states that one ought not to necessarily rely on respected authorities, as “[a]ny one who in discussion relies upon authority uses, not his understanding, but rather his memory” (Richter, 219). So, how does one come to the kind of understanding that Leonardo perceives as a necessary prerequisite to productively commenting on any given topic? There is only one way, and that is through experience.

To put it simply, for Leonardo “[w]isdom is the daughter of experience” and “[e]xperience never errs” (Richter, 217-218). This doesn’t mean that one cannot learn from other people, but rather that when learning from others one should never relinquish their own appreciation of experience as the ultimate provider of understanding. A respected authority may make any claim they like, but that claim must be provable in order for belief in it to rise from a mere opinion to the level of understanding. In order to test and (dis)prove any claim, one must necessarily rely on their own experience in doing so. For this reason, he writes that experience “…has been the mistress of those who wrote well” (Richter, Loc. 245-253) and “…the one true mistress”; those guided by experience “…look only for things that are possible…” (Richter, Loc. 261). Leonardo acknowledges that his “…proofs are opposed to the authority of certain men held in the highest reverence by their inexperienced judgements…” (Richter, Loc. 261), but explains that “…my works are the issue of pure and simple experience…” (Richter, Loc. 261), which “…never errs” (Richter, 217-218). His disagreement with the authorities mentioned was not a product of rebelliousness or stubbornness, but rather the only possible end resulting from his preferred means of learning; by experience. One can even come to understandings about nature, for Leonardo our creator and teacher, through experiences of it. He writes that, "[n]ature is full of infinite reasons which have not yet passed into experience" (Richter, 217). While further illustrating Leonardo’s belief (or as he would likely put it, understanding) that the law of nature is cause and effect, we may also catch a glimpse of his hope for the future. In writing “not yet”, perhaps he indicates a longing for (or even expectation of) a future time when the experiences of people can account for the “infinite reasons” or causes resulting in nature’s particular observable effects, so as to provide a true understanding of nature in all her complexity.

Setting aside dreams of the future however, Leonardo also interprets experience as the only mechanism through which humans can develop reliable arts and sciences. The process that ultimately results in these arts and sciences is multi-step. First, “sound rules” must be developed, and “…sound rules are the issue of sound experience…” (Richter, Loc. 305). After establishing rules informed solely by experience, one must then come to an understanding, as “…a clear understanding comes of reasons derived from sound rules…” (Richter, Loc. 305). Once understanding has been grasped, judgement will likely begin to improve, because “…good judgement is born of clear understanding…” (Richter, Loc. 305). Thus, for Leonardo, good judgement is at the core of the arts and sciences, as those reliable arts and sciences are in a literal sense provable judgements about the universe one lives in. For these reasons, Leonardo argues that “…sound experience [is] the common mother of all the sciences and arts” (Richter, Loc. 305). Leonardo clarifies his position further in writing, “…I consider vain and full of error that science which is not the offspring of experience, mother of all certitude, and which does not result in established experience, that is to say, whose origin, middle and end do not pass through any of the five senses” (Baring, 516-517).

In other words, science, in its entirety, must be based on experience. Experience absolutely must and can only occur as a result of passing through one of the five senses (sight, smell, sound, touch, or taste). Consider for a moment Leonardo’s statement that “[s]cience is the observation of things possible, whether present or past…” (Richter, 218). As noted earlier, those guided by experience “…look only for things that are possible…” (Richter, Loc. 261), so taken together the two quotes clearly communicate that experience (and by extension, science) accounts for everything that is possible. Experience must pass through one of the senses, so this can only be reasonably understood as Leonardo taking the position that everything which is possible must, by definition, be able to pass through one of the senses. Responding to fools who might argue that people should doubt their senses, Leonardo appropriately responds, “…if we doubt of everything we perceive by the senses, should we not doubt much more of what is contrary to the senses, such as the existence of God and of the soul, and similar matters constantly under dispute and contention?” (Baring, 516). I needn’t explain further here, as Leonardo’s words, heretical as they may be, speak for themselves.

Notebook Philosophy: Religious Concepts

Having covered Leonardo’s conception of experience as the sole precursor to understanding, let’s engage in a brief exploration of his thoughts on a variety of somewhat “loaded” topics. I write “loaded”, because controversial views on these specific topics could prove quite problematic for the safety of the individual presenting them, in the context of Renaissance Italy. Leonardo’s notebooks are filled with fables, aphorisms, and advice focused on the pursuit or embodiment of qualities that he perceived as desirable. These desirable qualities that Leonardo so often points or alludes to, which are exceptionally wide-ranging, seem a reliable indicator of what he perceived as “good”. The virtues he upholds range from the value of being productive (Richter, 221) to the importance of respecting all life forms (Richter, 216), but never incorporate the religious undertones so common among the authorities of his day. The same is true in Leonardo’s treatment of the concept of “evil”. Throughout his notebooks he uses the term “evil” to describe anything from a bad/unpleasant thing (Richter, 225, 261, 301, etc.), to a reprehensible tendency found in people (Richter, 208, 257, 263, etc.). Even something as seemingly innocent as poorly designed architecture is considered “evil” by Leonardo (Richter, 74). He treats heaven and hell similarly. Typically for Leonardo, heaven just refers to the skies (Richter, Loc. 4043, 112, 164, etc.). Sometimes he also uses it as an element to convey meaning when producing fables or artworks (Richter, Loc. 4072, 246, 262, etc.), but never provides the faintest of an indication that he believes in heaven as described by theologists. The same is true of his use of the concept of hell; it carries a certain negative association that Leonardo hopes to appropriate for his own uses (Richter, Loc. 4053, Loc. 4121, 315). The concept of divinity is also repurposed by Leonardo, as in his writing, “divine” simply means wonderful (Richter, 262). This again occurs in his description of saints, about which he writes, “…any one who is virtuous… these are our Saints on earth; these are they who deserve statues from us, and images…” (Richter, 317). For Leonardo, the saints deserving of appreciation and recognition are not necessarily holy in any way, but instead can act as models for and teachers of others.

Notebook Philosophy: Spirit

Clearly, Leonardo is content with using words that often have religious connotations, and divorcing them from their usual context. In doing so, he artfully challenges the validity of his contemporary authorities’ religious claims. This couldn’t be truer than in Leonardo’s redefinitions of both the spirit (spirito) and the soul (anima); first we’ll cover the spirit. For Leonardo, spirit can simply describe willpower (Richter, 261). Spirit can also describe the tendency of things. For example, the “…spirit of the elements…” is to return to their former state (Richter, 219-220), and the lion “…fights with a bold spirit…” (Richter, 240). Leonardo plainly provides his position on the spirit in writing, “…the definition of a spirit is a power conjoined to a body…” (Richter, 231). That being said however, there is quite a deal of nuance to Leonardo’s perception of this conjoined power. One feature of this perception is the argument that force “…is the child of physical motion, and the grand-child of spiritual motion…” (Richter, 109). He essentially means that something must have a desire and/or tendency to physically move before it actually does. What is more striking in Leonardo’s treatment of the spirit is his description of what it cannot be. For one, the spirit “…cannot move of its own accord, nor can it have any kind of motion in space…” (Richter, 231). Just making this claim was not enough for Leonardo, as in the following pages of Richter’s translation he provides an extensive proof of his argument. Feeling confident in the proof, he writes, “[w]e have proved that a spirit cannot exist of itself amid the elements without a body, nor can it move of itself by voluntary motion unless it be to rise upwards” (Richter, 231). I won’t detail exactly why Leonardo believes the spirit could rise upwards as his reasoning is quite complex, but do realize that he is only entertaining all reasonable possibilities. As he cannot disprove that the spirit could potentially move skyward, he presents it as the only way in which a spirit could possibly move, though in no way endorses this as the correct inference. In fact, his previously noted writing that the spirit “…cannot move of its own accord…” (Richter, 231), seems to indicate his tendency to believe that the spirit cannot move at all. If it were to move upwards, this would simply be the result of the formation of a vacuum, not any intentionality on the part of the spirit.

To reiterate, Leonardo is perpetually occupied with that which is possible, and this of course is true in his exploration of the spirit. As he acknowledges that there must be some impetus for movement prior to that movement taking place, and assigns that impetus to the spirit, he must grapple with an obvious question. If the spirit is a power attached to a body, what happens to the spirit when the body dies? In his typical rigor, Leonardo refuses to shy away from this conundrum. If the spirit were to rise in the air upon the death of its body, “…such a spirit taking an aerial body would be inevitably melt[ed] into the air…” (Richter, 231). He explains how the winds would “disunite” the spirit and diffuse it into all air its continually diluted essence was exposed to, causing it to become “dismembered” and “broken up” (Richter, 232). Leonardo is essentially saying that the spirit would quickly cease to exist the moment it became separated from the body. After providing more proof that the spirit could not move itself in any way after being diffused into air (Richter, 232), he also disproves the possibility that the spirit could speak (Richter, 232-233). Again, his argument is quite detailed and I won’t provide the specifics, but his conclusion is that, “…the wave of the voice passes through the air as the images of objects pass to the eye” (Richter, 233). Allow me to explain; in the same way that we could never see a spirit because it has no form, we could never hear a spirit because it has no voice. Perhaps the icing on this proverbial “heresy cake” could be Leonardo’s writing that anyone who believes spirits can move and/or speak is promoting the existence of “imaginary spirits” (Richter, 230). “Beware of the teaching of these speculators…” he writes, “…because their reasoning is not confirmed by experience” (Richter, 230). I won’t provide a detailed analysis of Catholic doctrine regarding the “Holy Spirit”, but Catholics believe that the “Holy Spirit” can both move (Genesis 1:2, Acts 2:2-4) and speak (Timothy 4:1-2, Acts 8:29, Hebrews 3:7, etc.) in the absence of a body. For logical reasons Leonardo must disagree, but he hopes not to be despised for the understandings his experience requires he come to. Remember, anyone who seeks to blame Leonardo “…is not considering that [his] works are the issue of pure and simple experience” (Richter, Loc. 261).

Notebook Philosophy: Soul

Having covered Leonardo’s perception of the spirit, we’ll now move on to his thoughts on the soul. It immediately must be noted that, for Leonardo, it is impossible to prove exactly what the soul (and for that matter, life itself) truly is (Richter, Loc. 312). Essentially though, the role of the soul is to keep the individual separated from all the other living things around them. We’ve already established that the spirit of the elements is to return to their former state. With this in mind, consider Leonardo’s writing that the spirit of the elements, “…finding itself imprisoned with the soul is ever longing to return from the human body to its giver” (Richter, 220). In other words, the soul acts as a prison for the body; it prevents the body from spontaneously dying. The soul does this because “[t]he [soul] desires to remain with its body, because, without the organic instruments of that body, it can neither act, nor feel anything” (Richter, 216) (here Richter mistranslates “L’anima” as “the spirit”, when Leonardo has distinct meanings associated with soul (anima) and spirit (spirito)). With respect to the soul and the body, Leonardo provides a clear hierarchy of the two. He writes, “…so much more worthy as the soul is than the body, so much more noble are the possessions of the soul than those of the body” (Richter, Loc. 237). This, of course, is because wisdom, which as we’ve covered “…is the daughter of experience” (Richter, 218), is to Leonardo “…the food and the only true riches of the mind” (Richter, Loc. 237). So, the soul is superior to the body, and wisdom superior to material riches, but what happens when the body dies? Leonardo would respond that, “[t]he soul can never be corrupted with the corruption of the body, but is in the body as it were the air which causes the sound of the organ, where when a pipe bursts, the wind would cease to have any good effect” (Richter, 216). Essentially, he means that when the body dies the soul becomes useless, but as it is not composed of the elements, it will not decompose.

In order to better understand the soul, we need to cover the “Common Sense”. The “Common Sense” is “…that part where all the senses meet” (sight, smell, sound, touch, and taste) (Richter, 102). This central meeting point is a singular physical part of the body located in/near the brain (Richter, 102). The senses feel and then transmit those feelings to the “Common Sense” (Richter, 102), but the “Common Sense” can also direct movement. Leonardo communicates the mechanism through which this “Common Sense” orders movement in writing, “…the joint of the bones obeys the nerve, and the nerve the muscle, and the muscle the tendon and the tendon the Common Sense” (Richter, 102). Basically, the “Common Sense” receives all information coming from the five senses, while also transmitting the instructions necessary for operation of the body. The “Common Sense”, after processing the inputs from the five senses, then gives rise to judgement. Leonardo explains this in writing, “…the judgement would seem to be seated in that part where all the senses meet” (Richter, 102). Now consider Leonardo’s proposition that “[t]he soul seems to reside in the judgement…” (Richter, 102). This means that we experience, those experiences are then processed by the “Common Sense”, that processing gives rise to judgement, and that judgement produces what Leonardo refers to as the soul. So, the soul consists of the sum-total of a person’s past judgements, held in the form of memories and impressions.

On that point, Leonardo writes of the soul, “…memory is its ammunition, and the impressibility is its referendary…” (Richter, 102) (a “referendary” is a referee). As a person moves through the world they have experiences, use those experiences to form rules, and use those rules to come to understandings (Richter, Loc. 305). As a result of these understandings, they then attain better judgement, as “…good judgement is born of clear understanding” (Richter, Loc. 305). Therefore, judgement initially gives rise to the soul and regularly feeds it, but the soul (again, read collection of understandings) will improve a person’s judgement, so long as the person is informed by “…a clear understanding… derived from sound rules…” (Richter, Loc. 305). This unique treatment of the soul gives rise to Leonardo’s distinction between an “act” and an “operation” of the human mind. “Discerning, judging, [and] deliberating are acts of the human mind” because “[e]very action needs to be prompted by a motive” (Richter, 217). The soul provides the memories and impressions which the judgement uses to make considerations, and the “Common Sense” provides sensory input to aid in said considerations, so these act as the motives for any judgement. However, “[t]o know and to will are two operations of the human mind” (Richter, 217). Knowing and willing function as the motive for the judgement to improve as a result of the soul’s knowledge (“to know”), or for the “Common Sense” to direct movement in response to the instruction of the soul (“to will”). “…[T]he sense waits on the soul and not the soul on the sense” (Richter, 102) because the soul acts as the motive and the judgement and/or “Common Sense” responds to said motive.

Notebook Philosophy: The Soul and God

Leonardo also understands the universe to have a soul, but in order to appreciate his treatment of this universal soul, we must first touch on his descriptions of God. Oftentimes, Leonardo uses God as an element to convey meaning in a fable or planned artistic depiction (Richter, Loc. 4118, 202, 256, etc). These uses of God, which are mirrored in his treatment of the devil (Richter, Loc. 4051, 300), simply take advantage of the common associations people make with such entities. Leonardo also refers to God in letters he wrote discussing a planned project (Richter, 307), as a formality with a patron (Richter, 314), and as a figure of speech (Richter, 311). It is overwhelmingly clear, however, that for Leonardo, nature is God. We’ve already covered Leonardo’s understanding that nature is responsible for the creation of men, putting into them their souls. You should also recall that Leonardo believes nature is both the source and cause of her own laws, and is responsible for producing her own existence. Leonardo provides even more confirmation of these understandings resulting from his experiences. Consider his writing that painting is “…the grandchild of nature, and related to God” (Richter, Loc. 3658). Here a relationship is drawn between God and nature, but not necessarily one that equates the two. Given the social climate in Renaissance Italy, Leonardo could not come out and directly state such a position. Instead, he cleverly communicated his message by writing elsewhere, “[w]e, by our arts may be called the grandsons of God” (Richter, Loc. 3680). If painting is the grandchild of nature, and people through their arts can be called grandsons of God, then nature must be God. If that doesn’t convince you, contemplate his more straightforward mention that theologians “…speak of nature or God” (Richter, Loc. 3715).

There is yet another, more beautiful way that Leonardo presents this incredibly heretical and naturalist message. The polymath writes of “…the mind of God in which the universe is included…” (Richter, 229), and on the sun, proffers that “…from it descends all vital force, for the heat that is in living beings comes from the soul [vital spark]…” (Richter, 118). To restate, our universe is contained within the mind of God, and the sun is the soul of our universe. Now, I’ve already mentioned that Leonardo believes “[t]he globe [is] an organism” (Richter, 167), but he has much more to say on this. Leonardo explains that, “…its flesh is the soil, its bones the arrangement and connection of the rocks of which the mountains are composed, its cartilage the tufa, and its blood the springs of water” (Richter, 167). He continues, “[t]he pool of blood which lies round the heart is the ocean, and its breathing, and the increase and decrease of the blood in the pulses, is represented in the earth by the flow and ebb of the sea…” (Richter, 167). In other words, the physical features of the earth are its body. This makes sense to Leonardo, as “[n]othing originates in a spot where there is no sentient, vegetable and rational life…” (Richter, 167). If the earth produces life, then it must be a living organism itself, according to Leonardo’s formula. We’ve already learned that the soul of our universe, and by extension the earth organism, is the sun. Leonardo also writes that, “…the earth has a [soul] of growth…” (Richter, 167) (Richter mistranslates “anima” as “spirit”). He notes, “… the heat of the [soul] of the world is the fire which pervades the earth…” (Richter, 168), meaning that the warmth required for life on earth is contained within the earth itself (and derives from the sun), though often it does “…find vent in baths and mines of sulphur, and in volcanoes…” (Richter, 168).

The theory presented by Leonardo has an incredible parallel with his description of the souls and bodies of individuals; allow me to explain. The soul of a person is, according to Leonardo, located at a specific point within the mind. The soul of the individual corresponds to the universal soul, the sun, located at a specific point in the mind of God (which contains the universe). The person’s soul must collaborate with the judgement and the “Common Sense” in order to move its body or produce anything. However, the “Common Sense” is “…that part of man which constitutes his judgement…” (Richter, 100) and “[d]iscerning, judging, deliberating are acts of the human mind” (Richter, 217). Given that the “Common Sense” and the judgement apply only to people, we will not find universal equivalents for them. As we just covered, the physical formations on earth (mountains, rivers, etc.) are compared to body parts by Leonardo, and these of course correspond to the body of the person. To wrap up the incredible parallel Leonardo draws between the mind of man and that of God, which exemplifies a more literal interpretation of the ages-old saying “that which is above is like to that which is below” (The Hermetica), let us discuss the organisms which live on earth. I’ll mention again Leonardo’s writing that “…the seat of the vegetative soul is in the fires…” (Richter, 168), by this he intends to say that the souls of all living things on earth come from the fires within the earth (which themselves come from the sun). Consequentially, everything on earth is provided the opportunity for individual life by the sun (including even the earth organism itself). Compare this to the way the soul of a person must provide instructions to the body in order for the body to move or create anything. Thus, the mind (our universe) of God (nature) corresponds to the mind of man, the soul of the universe (sun) corresponds to the soul of man, the body of earth (soil/flesh, bones/mountains, etc.) corresponds to the body of man, and the works of the earth (organisms on earth, by extension works of nature) correspond to the works of man. For Leonardo, we all are works of nature. We humans are tiny and temporary specks in the expanse of nature, which is our God.

Leonardo provides his puzzle of the soul for the curious student of his work, but he also recognizes how heretical this puzzle truly is. After all, to say nature is our God is to deny the Christian conception of God the father, to say the spirit cannot move or speak is to deny the Holy Spirit, to say “…those who have chosen to worship men as gods… have fallen into the gravest error…” (Richter, 118) is to deny Jesus Christ, and to say the soul “…ceas[es] to have any good effect…” (Richter, 216) upon the death of the individual is to deny the existence of heaven and hell. Perhaps the latter best explains why Leonardo writes that, “…the rest of the definition of the soul I leave to the imaginations of friars, those fathers of the people who know all secrets by inspiration” (Richter, 102). He also writes of friars, “[m]any have made a trade of delusions and false miracles, deceiving the stupid multitude” (Richter, 228). Contrast his description of friars as learning from imagination with his position that understanding results from experience. If friars know “secrets” through imagining and their followers through inspiration, then they must by definition be lacking in understanding (according to Leonardo’s formula). The next line of his writing is truly astounding, in no small part because it was intentionally mistranslated by the theologically inclined Jean Paul Richter. I won’t delve into the specifics of the Italian language, but a proper translation of the sentence reads, “I leave alone the sacred books because I know the truth” (adapted from Richter, 102)(see NOTE at end).

Leonardo’s understanding of nature as our God resulted in his strong distaste for those who reduce God into smaller, more manageable parts. He writes reprovingly of such people, “…they want to comprehend the mind of God in which the universe is included, weighing it minutely and mincing it into infinite parts, as if they had to dissect it!” (Richter, 229). Leonardo continues, writing that such fools are liable to, “…occupy [themselves] with miracles, and write that [they] possess information of those things of which the human mind is incapable and which cannot be proved by any instance from nature” (Richter, 229). The blistering critique expands in his writing, “…you deceive yourself and others, despising the mathematical sciences, in which truth dwells and the knowledge of the things included in them” (Richter, 229). Leonardo expands beyond general statements, and hones in on some of the specific “…contradictions of sophistical sciences which lead to an eternal quackery” (Richter, 219). One such “sophistical science” Leonardo despised was necromancy, of which he wrote, “…it can never have existed, nor will it ever exist…” (Richter, 231). Leonardo here blatantly disregards the Catholic teaching that necromancy absolutely does exist (Samuel 28:7-19). In concluding this section focused on Leonardo’s philosophy as detailed in his notebooks, I’ll leave the reader to dwell on the following words. “[T]he truth of things is the chief nutriment of superior intellects…”, “[b]ut you who live in dreams are better pleased by the sophistical reasons and frauds of wits in great and uncertain things, than by those reasons which are certain and natural and not so far above us” (Richter, 221).

Leonardo’s Secrecy and Determination

While Leonardo’s philosophy is certainly present in his notebooks, it can also be found in his art. After all, as Leonardo wrote, “… often a master’s work resembles himself” (Richter, Loc. 3297). For obvious reasons though, he couldn’t depict these philosophical themes without risking punishment. Leonardo had an acute awareness of the risks associated with overenthusiastic sharing of one’s thoughts or ideas. In one fable, he describes an oyster being devoured by a crab as analogous to “…what happens to him who opens his mouth to tell his secret… [h]e becomes the prey of the treacherous hearer” (Richter, 244). Leonardo reveals further this understanding in his writing that, “[h]e who offends others, does not secure himself” (Richter, Loc. 4129). Perhaps making Leonardo’s addition of these themes less surprising, though far bolder, is the fact that he had developed something of a reputation as a heretic. One such recognizer of these heretical tendencies is Giorgio Vasari, a Renaissance biographer of Leonardo, who wrote in 1550 (three decades after Leonardo’s passing) that “he created in his mind such a heretical concept that it did not come close to any religion, perchance esteeming being a philosopher much more than being a Christian” (Vasari, translated with Google Translate). Leonardo even found himself prevented from entering the hospital at Santo Spirito due to a charge that he was “…[a] heretic and cynical dissector of cadavers” (Benesch, 1943). We also have an indication that Leonardo was once jailed for the content of his art, though the specific reasons for this imprisonment are not known. He writes in his Codex Atlanticus (680r) that, “[w]hen I made a Christ Child you put me in prison, and now if I show him grown up you will do worse to me” (salvatormundirevisited.com, n.d.).

Leonardo clearly had a drive to immortalize his studies. Consider his writing (as mentioned earlier) that one should “[a]void studies of which the result dies with the worker” (Richter, 221) alongside his comment that “[w]hat is fair in men, passes away, but not so in art” (Richter, Loc. 3653). He likely believed that representing his philosophy through his art was the only way he could ensure his understandings were appreciated by students of his work. Leonardo was a dreamer, a man who longed for a time when people would not be prohibited from pursuing their studies freely by overbearing authority figures. Perhaps this was the sentiment he hoped to capture in writing “[o]ne’s thoughts turn towards hope” (Richter, Loc. 4129) next to a drawing of a caged bird. The reader may find it difficult to accept that Leonardo would take a risk so extreme as imbuing heretical concepts in works commissioned by religious authorities. I would like to remind these readers that Leonardo was both resolute and patient. On his determination we read, “[o]bstacles cannot crush me… [e]very obstacle yields to stern resolve… [h]e who is fixed to a star does not change his mind” (Richter, Loc. 4088-4095). Leonardo acknowledges the importance of patience in writing that, “[h]e who wishes to be rich in a day will be hanged in a year” (Richter, 223). To reiterate, he was forced to make his hidden meanings complex enough so as to conceal them from the authorities of his day. As a result of this, one must engage in detailed analyses of his art to appreciate them. Thankfully, Leonardo provides something of a guide for anyone who would like to uncover the hidden meanings in his work for themselves. Given the introduction to his philosophy you’ve now received, the readers may enjoy using this guide and attempting to appreciate these themes for themselves, in the absence of any further tips from my writing. “The organ of sight is one of the quickest, and takes in a single glance an infinite variety of forms; notwithstanding which, it cannot perfectly comprehend more than one object at a time. For example, the reader, at one look over this page, immediately perceives it is full of different characters; but he cannot at the same moment distinguish each letter, much less can he comprehend their meaning. He must consider it word by word, and line by line, if he be desirous of forming a just notion of these characters. In like manner, if we wish to ascend to the top of an edifice, we must be content to advance step by step, otherwise we shall never be able to attain it” (A Treatise on Painting, Loc. 1624).

Leonardo the Anatomist

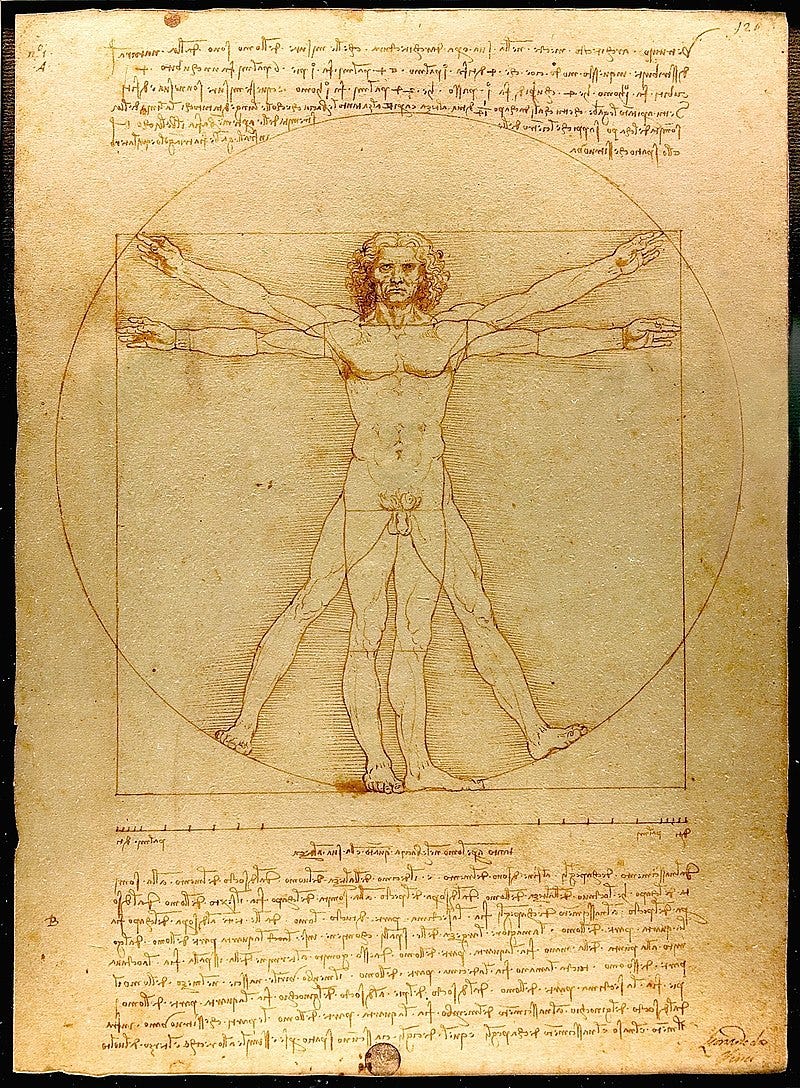

A couple more topics must be covered before we begin our exploration of Leonardo’s latent legacy. Some of the hidden meanings in his art revolve around intentional anatomical alterations. As Leonardo was an expert in anatomy, one must always pay close attention when he makes what appears to be an anatomical mistake. To support the reader in appreciating the intentionality behind some of the anatomical disfigurations in his art, I’ll briefly summarize Leonardo’s knowledge of the human body and ability to portray it precisely. His notebooks are filled with anatomically accurate depictions of nearly every part of the human body, as well as those of various animals. Leonardo, of course, was only able to do this so well because he had access to bodies for dissection. In fact, it is estimated that in a span of less than twenty-five years he undertook more than thirty dissections of different human bodies (Perloff, 2013). Astoundingly, Leonardo’s depictions are so true-to-life that anatomy professors today still use them as guides during human dissections, and current anatomy textbooks often contain them as well. In 2013, The Queen's Gallery at the Palace of Holyrood presented an exhibition which compared Leonardo’s anatomical drawings to modern scans done by MRIs and other technologies. The gallery reported that the comparison demonstrated the drawings had a “startling accuracy”. “Had [the drawings] been published at the time”, a spokesperson for the gallery explained, “they would undoubtedly have been the most influential work on the human body ever produced” (dailymail.co.uk, 2012). It shouldn’t be lost on us that Leonardo spent so many painstaking hours hunched over odorous corpses in the dark, drawing what he saw. Only the dedication of a man genuinely desirous of both understanding and accurately depicting the body can explain Leonardo’s efforts and successes in this task, most popularly memorialized by his Vitruvian Man. Considering this expertise, when we do identify an inaccuracy in Leonardo’s art, we must err on the side of assuming intentionality, while always leaving room for the possibility of unintentional error.

(Wikipedia) Vitruvian Man

Leonardo and St. John the Baptist

The last topic we have to cover before exploring Leonardo’s philosophy in his art, is, somewhat surprisingly, John the Baptist. Leonardo chooses to appropriate the character of John the Baptist, transforming John and a symbol commonly associated with him into a vehicle for communicating the philosophy that nature is our God. He does this by associating a hand gesture commonly found in depictions of John the Baptist (the pointed index finger) with nature. You might be wondering, why would Leonardo choose John instead of any other character? The reason seems to be threefold. Firstly, John is commonly found in religious art, and thus Leonardo discovered in John a reliable conduit for conveying hidden meaning in otherwise more conventional representations of biblical stories. Leonardo surely knew that the majority of artistic commissions sought by wealthy Catholic patrons in his time would be for religious scenes, so his choice of John is quite understandable. A second reason for Leonardo’s choice of John the Baptist is John’s close relationship with nature. Both the descriptions of John in scripture and depictions of him in art, more so than any other character in the New Testament, make central this relationship. “I am the voice of one calling in the wilderness…” (John 1:23, NIV), says John, the man who lived perpetually clothed in camel’s hair, and consuming only locusts, grasshoppers, crickets, and wild honey. Rather than Jesus baptizing with the “Holy Spirit”, John simply baptizes with water. The relationship between John and nature shines through beautifully in the frequency with which he is painted in nature scenes, a feature of many religious artworks produced centuries before Leonardo’s time. Leonardo’s final reason for choosing John the Baptist was the hand sign so commonly associated with him, the raised index finger. Leonardo imbued the raised index finger with a new, and very specific meaning, which is discernible throughout a variety of his artworks. Such a confluence of factors made John the Baptist an ideal specimen for appropriation, and Leonardo fittingly capitalized on this opportunity.

Adoration of the Magi

(Wikipedia)

Leonardo worked on his Adoration of the Magi in the year 1481, under the commission of Augustinian monks. The work depicts a scene described in the Gospel of Matthew, where three kings or wise men shower the newly born Jesus with frankincense, gold, and myrrh. The work is a treat to puzzle over, offering a plethora of figures and forms ripe for interpretation. The foreground of the painting represents the new, Christian world, inaugurated by the birth of Jesus and replacing the old pagan order, which is represented in the background by various battling horsemen and a crumbling building, thought to allude to the Basilica of Maxentius (which according to myth crumbled on the date of Jesus’ birth). Our focus in this painting will be on a small figure, which to my surprise, has essentially been completely overlooked by art historians to date. The figure can be found at the base of the large tree near the center of the painting, and is pictured below.

(Wikipedia, cropped)

Immediately, you’ll likely notice the hand with a raised index finger, elevated above the head of the figure just to the right of the tree. Now, adjust your gaze and focus on the base of the tree; pay attention to the root structure. Surely, now you’ve noticed that the figure’s arm extends from its sleeve, but that rather than taking the form of a typical arm, it becomes a root and merges with the root structure of the tree. See the photo below for close-ups of this section on both the older (left) and restored (right) versions of the painting.

(haltadefinizione, cropped)

(haltadefinizione, cropped)

Here, Leonardo has taken the symbol commonly found in depictions of John the Baptist (the raised index finger) and associated it with nature, a concept already closely related to John as described in the Gospels. Recall Leonardo’s philosophy that the bodies of men are works of nature (Richter, Loc. 2991). Here, Leonardo is merging the body of the person with nature quite literally, thus conveying the exact same sentiment. Shift your eyes back to the raised finger for a moment, as shown below.

(haltadefinizione, cropped)

While at first glance the raised finger appears standard, upon further inspection the finger has no fingertip. Instead, it extends to a freakish length before ultimately fading into space, merging with nature in a manner not dissimilar to that of the figure’s other arm. When considering these anatomical errors as either intentional or accidental, we are forced to discredit the possibility that a master like Leonardo should have made these brushstrokes accidentally. The sleeve of the arm clearly is pulled back, and the arm/root which descends into the tree is very obviously connected to that arm, which itself is connected to the figure’s shoulder. These are not accidents, but rather intentional additions meant to accomplish two objectives. The first is to associate John the Baptist with nature as a creative power, through connecting John’s characteristic raised index finger with nature’s status as the creator of men. The second is to present the same philosophy detailed in Leonardo’s notebooks; men are works of nature. Having covered this painting, we’ll now move on to Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks.

Virgin of the Rocks

The Virgin of the Rocks is two paintings completed by Leonardo, which I will be referring to as the Louvre (estimated to date to around 1483-1486) and London (estimated to date to around 1495-1508) versions. The paintings were commissioned by the Confraternity of the Chapel of the Immaculate Conception, and the Louvre version is understood to be the earlier of the two, though as centuries have passed since these works were created, there is some dispute as to their dating. The commission initially called for a very specific scene, but Leonardo seems to have bucked these requests. This choice apparently upset the Confraternity, and a dispute arose over payment. The details of this dispute are slightly tortuous, but the end result is generally understood to be Leonardo’s taking the Louvre version from the Chapel and providing the London version as a replacement. This story is not important to my interpretation of these works, and art historians are not in agreement on the specifics, but hopefully it nevertheless can give the reader some idea of these works’ histories. Having provided a slight introduction, feast your eyes on Leonardo’s masterpieces.

Louvre Version

London Version

(Wikipedia)

First, let’s identify the characters in the picture, from left to right. Kneeling on the left is John the Baptist, easily recognizable by his garment of camel hair and long, thin reed cross in the London version, but essentially identical to the other baby in the Louvre version. In the center is, of course, the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus. The baby under Mary’s hovering hand is Jesus Christ, and the angel to her side is Uriel, the Archangel of Knowledge. You might be wondering, why these characters and this setting? The answer is somewhat complex, but basically the paintings are a merger of two extrabiblical stories with Leonardo’s imagination. The first story comes from the non-canonical Gospel of James, which describes the efforts of Joseph to protect Mary and Jesus. Joseph settles the family in a cave, and the Virgin of the Rocks is generally understood to depict a moment after Jesus’ birth, but before his and Mary’s departure from the cave. However, Leonardo merges this story with a legend that John the Baptist was escorted to Egypt by the angel Uriel. The scene therefore betrays Leonardo’s surprising familiarity not only with canonical scripture, but also with relatively obscure Christian texts and legends. Now we’ll explore more specifics of the paintings. First, we’ll be focusing on the Louvre version, and then we’ll compare it to the London version. Take a look at the angel Uriel’s hand, which in the Louvre version, is pointing directly at John the Baptist.

(Wikipedia, cropped)

The raised index finger, which Leonardo has already associated with the formative power of and man’s interconnectedness with nature, is now being wielded by Uriel, the Archangel of Knowledge. Now, Leonardo has connected the formative power of nature to the embodiment of wisdom, while also affirming John the Baptist’s relationship to the raised finger. No characters have halos, and Uriel’s wings seem subdued, almost as if blending into the rocks behind her. Also, John the Baptist looks nearly identical to Jesus, and this should be interpreted as an attempt to call attention to the closeness and essential sameness between nature (represented by John when associated with the raised index finger) and God (represented by Jesus). Uriel locks eyes with the viewer, as if beckoning you to search for the source of wisdom in this work. Let’s focus on some other features: marvel at the flora and geology in the Louvre version. The Renaissance art historian and geologist Ann Pizzorusso explains that “[t]he botany in the Louvre version is perfect, showing plants that would have thrived in a moist, dark grotto…” (theguardian.com, 2014). She continues detailing the incredibly accurate rock formations, “[t]o the right of the virgin’s head is weathered sandstone, and above it is a contact surface with a strata of diabase and above that is spheroidal sandstone” (theguardian.com, 2014). The horticulturalist John Grimshaw comments on the flora in the Louvre version, “[t]here’s a very recognisable iris, a Jacob’s Ladder, a nice little palm tree, all sorts of well-observed bits of vegetation there – and proper plants” (theguardian.com, 2014). In addition to the hyper realistic flora and fauna, we must say the same of the lighting in the painting. The scene appears, above all else, natural.

Detail of a rock formation

Detail of flora

(Wikipedia, cropped)

Before moving on to explore the London version, direct your eyes towards the rock formation to the left of Mary’s head. You’ll notice that Leonardo has painted what appears to be a hand, rising out and composed of nature, of course communicating his belief that “[t]he globe [is] an organism” (Richter, 167).

(Wikipedia, cropped)

Compare these features to the seemingly similar London version. Firstly, look where once was Uriel’s hand with extended index finger. In the London version, the hand is nowhere to be found.

(Wikipedia, cropped)

Leonardo uses this removal to illustrate the association of the raised finger with nature’s creative power and status as the source of all true knowledge (as we can only gain understanding through our experiences of nature). Watch as, with the subtraction of Uriel’s raised finger pointed at John, the entire painting changes. One such change is to the characters, as Mary, Jesus, and John now have halos above their heads, indicating a departure from the natural and movement towards the religious conception of our world and existence. John the Baptist also holds a reed cross and wears camel’s hair, making him look very different from Jesus, and thus eliminating any commentary on the relationship between nature and God. Also notice that, in contrast to the Louvre version, Uriel no longer encourages the viewer to engage with the painting. Now, look closely at the geology and flora in the London version. On the botany, Ann Pizzorusso, who voiced such high praises for the Louvre version, writes, “…the plants in the London version are inaccurate… [s]ome don’t exist in nature, and others portray flowers with the wrong number of petals” (theguardian.com, 2014). The horticulturalist John Grimshaw, who also spoke highly of the Louvre version, feels similarly about the London version. “It’s very striking, because they go against everything that Leonardo’s always done in terms of his botanical art. They’re not real flowers. They’re odd concoctions, like a half-imagined aquilegia. And looking at the daffodil, for example, the flowers are OK, but the plant is not right” (theguardian.com, 2014). Pizzorusso has similar thoughts on the geology in the London version, and writes, “[t]he rocks are all angular and blocky, with no distinctive texture” (theguardian.com, 2014).

Detail of a rock formation

Detail of flora

(Wikipedia, cropped)

Unfortunately, Pizzorusso and Grimshaw were unaware of the reason for these differences in the London version. As they could not explain Leonardo’s intentionally butchering his depictions of nature despite his reputation (and personal value) of striving for accurate portrayals in his works, the researchers conclude that the London version is not a work of Leonardo’s. However, in doing this they disregard the scholarly consensus that the London version is indeed by Leonardo’s own hand. My hope is that, upon engaging with this theory, those researchers will feel comfortable considering the London version to be a genuine Leonardo. Of course, my theory is reinforced by the strange, otherworldly lighting present in the London version, which starkly contrasts with that of the Louvre version. Lastly, note that the hand protruding from nature has been removed in the London version; after all, in a strictly religious scene there is no place for the proposition that nature is the creator of man and source of knowledge, or that earth itself is an organism.

(Wikipedia, cropped)

The Holy Children Embracing

The next artwork we’ll cover is a sketch found in Leonardo’s notebooks, known as the Holy Children Embracing. This sketch (or a similar version) has inspired dozens of works by numerous artists depicting a nearly identical scene. It must be noted, however, that Leonardo was the first to portray Jesus and John in such a unique embrace.

(rct.uk, cropped)

Firstly, notice the similarities in posture between Jesus and John as pictured in this sketch, and Jesus and John in Virgin of the Rocks.

John the Baptist in Virgin of the Rocks, Louvre

Jesus Christ in Virgin of the Rocks, Louvre

(Wikipedia, cropped)

John is resting on his thigh in the Holy Children Embracing, but his legs remain bent in comparable proportion to those of John in Virgin of the Rocks. John’s right arm also extends forward at essentially the same angle in both works. Looking to Jesus, we notice that he sits in the exact same position, relying on his left arm for support by leaning it against the rock. Of course, the two children are also locking eyes in similar fashion. Looking to the background of the works you will notice corresponding rock formations, and when considering these factors in conjunction, Leonardo is clearly attempting to establish a relationship between the Holy Children Embracing and the Virgin of the Rocks (Louvre), because he hopes to convey a similar philosophical theme. As noted earlier, Leonardo uses the character of John the Baptist as a stand-in for his understanding of nature, in times when John is associated with the raised index finger. In the Holy Children Embracing, a parallel is drawn with the Louvre version of Virgin of the Rocks (and not the London version, as John wears no camel hair and totes no cross) to indicate Leonardo’s inability to distinguish between nature (John) and God (Jesus). While there is no raised index finger in the Holy Children Embracing, the parallels with the Louvre version communicate that we are looking at a similarly philosophically imbued work, and not a strictly religious scene like that of the London version. Jesus and John in the Holy Children Embracing thus embody the essential sameness of nature and God, and perhaps unsurprisingly, we find the same theme in Leonardo’s The Last Supper.

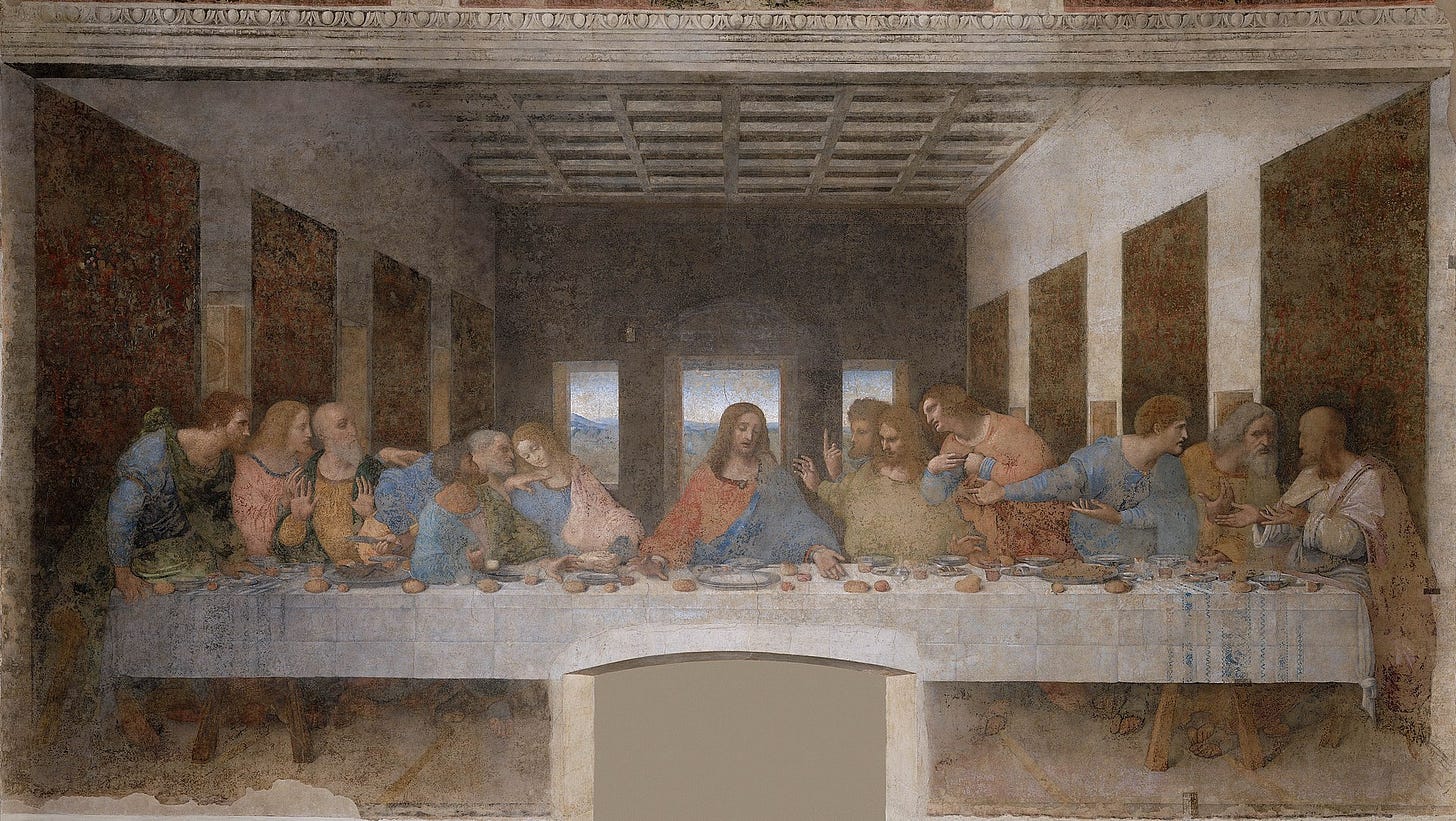

The Last Supper

Apart from the Mona Lisa, The Last Supper is surely Leonardo’s most famed artwork, and one which he likely worked on from 1495-1498. Ludovico Sforza (Duke of Milan) commissioned the fresco, which was to be located in the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie. The scene depicts Jesus Christ with his twelve apostles, in the moment just after Jesus has announced that one of those apostles will betray him.

(Wikipedia)

Many different reactions can be identified among the apostles, but we will focus specifically on one apostle, Thomas Didymus. Thomas can be located just to the left of Jesus’ head (from Jesus’ perspective), and his head is closer to Jesus’ than any other apostle’s.

(Wikipedia, cropped)

(Wikipedia, cropped)

Strangely, in the moment just after Jesus has announced his own imminent betrayal, Thomas appears unbothered. Thomas’ face is plain and determined, he stares directly at Jesus with a stone-cold expression. In a moment when one would expect Thomas to react in disgust, anger, or confusion, he instead simply raises his index finger. Of course, the raised index finger, for Leonardo, signifies nature’s position as our creator and the source of true knowledge. In the context of Thomas’ raising it, however, the finger takes on yet another layer of meaning. Christians often refer to this apostle as “Doubting Thomas”, because of a story told in the Gospel of John. In John 20:24-29 we learn that, as Thomas has not seen Jesus risen after the crucifixion, he is not a believer. We read that Thomas said, “[u]nless I see in his hands the mark of the nails, and place my finger into the mark of the nails, and place my hand into his side, I will never believe” (John 20:25, NIV). Thomas ultimately becomes a believer when he is given the opportunity to thrust his finger into Jesus’ side, but Thomas’ raised finger is of course a symbol of his doubt. Jesus responds, in effect criticizing those like Thomas, by saying “[b]lessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed” (John 20:29, NIV). Thomas is not the kind of follower Jesus would hope for; he does need to see to believe. Compare this to Leonardo’s conception of the acquisition of understanding as resulting from one’s experiences. Leonardo, like Thomas, needs to see in order to believe (or rather, experience in order to understand). For this reason, Thomas is the ideal apostle to communicate the message that nature is our creator.

Already, you’ve noticed that Thomas’ head is closer to Jesus’ than that of any other apostle. Let’s consider this in light of the meaning of Thomas’ name. The name “Thomas Didymus” is in fact translatable as “twin twin”, as the roots of Thomas in Aramaic and Didymus in Greek both mean “twin”. Surprisingly, Thomas was thought by some early Christians to be the twin of Jesus Christ. According to the Acts of Thomas, a noncanonical Christian text datable to the third century CE, Thomas is Jesus’ identical twin. As Leonardo was familiar enough with noncanonical Christian texts to develop a novel interpretation of the Gospel of James (which informed his Virgin of the Rocks), it is not unreasonable to assume he was familiar with the tradition that treated Thomas as the identical twin of Jesus, and even imbued Thomas with spiritual powers that put him into similar (though distinct) standing with Jesus himself. I won’t delve into the Acts of Thomas and its specific portrayals, as they are tangential; what is most important is Thomas’ status as the twin of Jesus. Again, this status can be understood simply via the translation of Thomas’ name (and Leonardo was a student of Greek), though it is possible that Leonardo was aware of the tradition which presented Thomas with a divine role himself. Now, in addition to Thomas’ (who represents the twin of God) head being closest to Jesus’ (who represents God), one may notice that Jesus’ hand seems to be reverencing Thomas’.

(Wikipedia, cropped)

If the message remains unclear, allow me to explain. Jesus (God) sits closest to Thomas (the twin of God) and raises his index finger, which represents doubt of that which one has not experienced (corresponding to the story of “Doubting Thomas” in the Gospel of John), alongside the creative power of nature (corresponding to Leonardo’s past works). In other words, nature is the twin of God, and one will come to this conclusion by trusting one’s own experiences.

The Burlington House Cartoon and the Painting of The Virgin and Child with St. Anne

Moving on from The Last Supper, we’ll turn to Leonardo’s cartoon, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist (which I’ll refer to as The Burlington House Cartoon), and his painting, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne. Leonardo is thought to have worked on The Burlington House Cartoon from either 1499–1500 or 1506–1508, and it was likely completed as a preparatory drawing for a painting that is no longer extant (if indeed the painting was produced). His painting of The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (1501-1519) was done for the Church of Santissima Annunziata as an altarpiece commission, though the work remains unfinished. The two works are similar to his Virgin of the Rocks in that the differences between them betray the philosophical themes present in the cartoon, but absent from the painting (analogous to the Louvre and London versions, respectively).

(Wikipedia)

Beginning our analysis with The Burlington House Cartoon, first let’s identify the characters. Furthest to the left is the Virgin Mary, and sitting with her is Mary’s mother, St. Anne, who raises her hand with extended index finger. Jesus Christ lays sprawled out across the women’s laps, and reaches out to touch the chin of John the Baptist, with whom he also locks eyes. Immediately, the viewer may notice a distinction between this work and Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks (Louvre) and Holy Children Embracing; John and Jesus are no longer difficult to distinguish, and appear to be different ages. In the cartoon Leonardo chooses another, more subtle avenue, to illustrate his understanding of the relationship between John (nature) and Jesus (God). Take a moment to puzzle over the legs of Mary and Anne.

(Wikipedia, cropped)

The longer one looks at these legs, the more challenging they become to associate with a specific body. One possibility is that the two legs furthest to the left are Mary’s, and the two furthest to the right are Anne’s. However, it seems equally likely that the legs furthest to the left and second from the right are Mary’s, while the legs second from the left and furthest to the right are Anne’s. This blending of the legs, a task surely only accomplishable by a master like Leonardo, is noticeable also in the fabric of the women’s clothing.

(Wikipedia, cropped)

The blending of the bodies of Mary and Anne should be interpreted as an allusion to the relationship between John (nature) and Jesus (God). This relationship is present in the work because Leonardo includes the raised index finger of Anne’s left hand, as pictured below.

(Wikipedia, cropped)

As Jesus stares into John’s eyes and the index finger extends itself in the background, Mary and Anne’s bodies blend into each other. This conveys the united, inseparable relationship between nature and God. Considering the presence of this element in the drawing, Leonardo could safely forego his slightly more obvious depictions of John and Jesus as appearing identically. Expectedly, the symbolism disappears entirely once the raised index finger is removed from the equation (as with the London version of Virgin of the Rocks), and John himself is even removed as well.

(Wikipedia)

The concurrent subtractions of both John the Baptist and Anne’s raised index finger should hopefully win over any reader as of yet unconvinced of the clear association between John and the raised finger. Notice also how the blending of Mary and Anne’s bodies has completely disappeared. Jesus now looks to his mother rather than nature personified as John, and he now grips a lamb, prefiguring his sacrifice. Thus, a philosophical statement (the cartoon) is replaced with a purely religious scene (the painting), and Leonardo once again communicates his understanding of nature as our God.

Saint John the Baptist and Angelo Incarnato

Fittingly, the grand finale of philosophical themes discoverable in Leonardo’s art (at least, those focused on nature) is to be found in his final work, Saint John the Baptist (1513-1516). The subject of the painting stares intently at the viewer, with a mouth stretching into a deviant grin. John thrusts towards the sky his pointed index finger, while curling his left arm towards his chest, at which he points his index and middle fingers.

(Wikipedia)

We’ve already identified the meaning of the raised index finger, but what should we think of the two fingers pointed towards John’s chest? Jesus Christ is regularly pictured in religious art predating Leonardo, where he uses his raised index and middle fingers to bestow blessings. Leonardo takes advantage of this imagery in two of his works, where he depicts Jesus Christ blessing John the Baptist.

Virgin of the Rocks (Louvre)

The Burlington House Cartoon

(Wikipedia, cropped)

Considering this, we should accept that Leonardo has established a precedent of Jesus Christ (representing God) blessing John the Baptist (representing nature when associated with the raised index finger) with his middle and index fingers. Here, in Leonardo’s Saint John the Baptist, John has replaced Jesus and now blesses himself. This should be perceived as conclusively communicating Leonardo’s understanding that nature is God. Perhaps the overwhelmingly heretical message contained in this painting was sensed by future censors of Leonardo’s work, as those censors added in the camel’s hair and reed cross which initially were absent from the painting. In doing so, they nonetheless fail to neutralize Leonardo’s incredible philosophical imbuement within the portrait. One finds a different, but similar attempt to censor Leonardo’s work in the attempted erasure of the penis on a sketch known as the Angelo Incarnato.

(Wikipedia)

Perhaps the erect penis, smudged by a failed attempt at erasure, offended someone with more traditional theological sympathies. The sketch is obviously related to Leonardo’s Saint John the Baptist (notice the raised index finger), and makes clearer the attempt to portray a hermaphrodite. The breast of the Angelo Incarnato is decidedly female, despite the presence of a male member. While Leonardo couldn’t portray personified nature as a hermaphrodite in all his works (on account of the conventions associated with depictions of John the Baptist), he also did so in Adoration of the Magi.

Adoration of the Magi

(Wikipedia, cropped)

From these three instances of personified nature shown as a hermaphrodite, I gather that Leonardo perceives nature’s essence as nongendered and all-inclusive. This understanding of course challenges the Christian belief in God as a male deity (God the Father, God the Son).

In Conclusion